As we thrash out the Voice, we’ve lost Archie Roach, one of the most eloquent voices of all

The First Nations singer-songwriter Archie Roach, who died last week after a long illness, was not just an extraordinary Australian artist, community worker, Gunditjmara-Bundjalung senior elder and loving father and foster father – he was foremost a truth-teller.

That was in evidence from the very beginning of his music career when, in 1989 and still unknown to a mainstream audience, he was invited to perform at the Melbourne Concert Hall by Paul Kelly and the Messengers. He ended his short set that night with a heart-wrenching recollection of the experiences of the stolen generations with his song Took the Children Away.

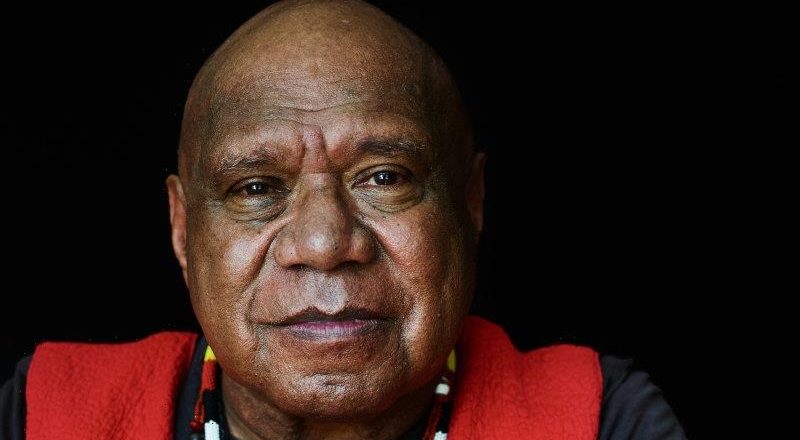

The late Archie Roach.Credit:Kristoffer Paulsen

“The welfare and the policeman said you’ve got to understand – we’ll give them what you can’t give. Teach them how to really live. Teach them how to live, they said. Humiliated them instead. Taught them that and taught them this. And others taught them prejudice. You took the children away.”

As Kelly would later recall, the audience sat there stunned. “He finished the song and there was still dead silence … Archie thought he’d bombed, that everybody hated it, so he just turned and started to walk off-stage.

“And as he walked off, this applause started to build and build and build. It was this incredible reaction,” Kelly said. “I’d never seen it before – people were so stunned at the end of the song that it took them a while just to gather themselves to applaud.”

Roach later described it as “the most amazing experience I ever had”. The song not only launched his career as the centrepiece of his 1990 debut album, Charcoal Lane, it subsequently became an anthem for First Nations reconciliation, for restorative justice and, as he would later discuss so eloquently, for honesty about one of the grimmest chapters both in his personal history and in the history of our nation.

The announcement of Roach’s death came as the Garma Indigenous cultural festival in the Northern Territory was in full swing. As Prime Minister Anthony Albanese loosely sketched out his plans to enshrine in the Constitution a First Nations Voice to parliament, we were reflecting on Roach’s vast cultural contribution and the themes he explored, among them colonialism, dispossession, the stolen generations, intergenerational trauma, racism and institutional brutality.

Albanese took to Twitter to honour Roach, describing him as a “national truth-teller”. Telling the truth about our past and the signing of a treaty with Indigenous Australians are both required by the Uluru Statement from the Heart, and are part of the policy that the government took to the election. How these fit with the Voice are among the many questions left open by Albanese’s speech and subsequent statements.

There remains a great deal of disagreement and political division in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community on many aspects of Albanese’s policies. He sees the Voice as “one of the steps in our nation’s journey of healing”. But some, such as Coalition senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, have already described the Voice proposal as paternalistic symbolism, while others, including Greens Senator Lidia Thorpe, Tasmanian activist Michael Mansell, and former Labor president Warren Mundine, are sceptical for other reasons.

As a nation, we might be in for a long, political and sometimes stultifying bureaucratic process as these things are thrashed out. But if Archie Roach’s honesty tells us anything, it’s that these matters are not just of the head – they are of the heart. And at the centre of it all is telling, and hearing, the sometimes confronting stories of our shared past.

Gay Alcorn sends an exclusive newsletter to subscribers each week. Sign up to receive her Note from the Editor.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article