CHRIS BRYANT: Tragedy that led me to explore my family tree

CHRIS BRYANT: Tragedy that led me to explore my family tree – and my links to a quiet hero of the Hebrides

Standing beside the beautiful sculpture of a coiled rope overlooking the harbour at Stornoway, I had not expected deep emotions to wash over me.

It was my first time on the Isle of Lewis, yet this simple memorial to a terrible tragedy stirred in me an unlikely and intensely personal sense of homecoming.

For bound within the artwork’s tight coils are the strands of my own family’s remarkable connection to a seminal point in Lewis history about which, until quite recently, I had little knowledge.

From where I stood, the views draw the eye out to sea to a lone stanchion marking the spot of the Iolaire disaster.

Welsh MP Chris Bryant recently discovered family links to the Isle of Lewis and the Iolaire disaster

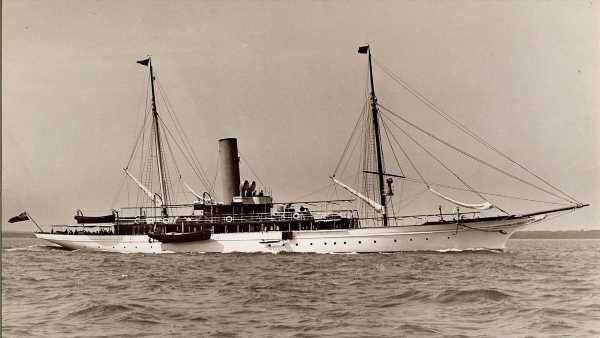

The Iolaire, inset, was commandeered to take men home from the war but sank off Lewis

Memorial to the MP’s great-grandfather

Growing up as a child in south Wales, I was dimly aware that a distant family member had a connection to what remains – more than a century on – the worst peacetime calamity in British naval history.

What I hadn’t appreciated until this point was that an astonishing act of selfless bravery performed by one of my relatives, John Finlay MacLeod, would help save the lives of 40 souls trapped aboard the sinking vessel.

Equally unexpected was that my efforts to chart my ancestor’s tale of heroism should uncover relatives I never knew existed and forge friendships I hope will last a lifetime.

The story begins in late December 1918, when John Finlay, who was my great-grandfather Donald’s younger brother, joined hundreds of young Lewis men, who had served in the war and were finally being allowed home for a few days’ rest over Hogmanay.

It was a long journey from Southampton for many of them, but they reached Kyle of Lochalsh on New Year’s Eve. Desperate to be home, they clambered on board one of two waiting ships.

One was the Iolaire, a millionaire’s yacht that had been commandeered by the Ministry of Defence.

Early that evening it set sail for Stornoway with half its usual crew and more than 280 passengers.

It was horribly overcrowded and the weather was wild but the men didn’t mind – they were going home.

Disaster struck in the early hours of New Year’s Day as they approached the harbour at Stornoway when the ship ran aground on notorious rocks known as the Beasts of Holm.

They were only yards from the shore, but it was a filthy dark night and the ship’s searchlight wasn’t working.

A gale was blowing. It was bitterly cold and vast waves were breaking on the rocks. That was when they found that the lifeboats were useless and sank.

It was then John Finlay MacLeod, a boatbuilder from Ness who had trained other sailors in the Royal Navy, took his life in his hands.

Wrapping a rope around his wrist, he leapt into the icy waters and could only pray that if he timed it right the wave would not dash him to pieces on the rocks but carry him to shore.

By a miracle he made it and soon another man followed on the rope with a thicker hawser.

One by one, men made their way clinging desperately to the hawser. Many lost their grip and disappeared under the waves. But 40 made it across before it snapped and the ship sank with the loss of all remaining life, many trapped below deck.

For days families came down to the beach to identify the bodies of their loved ones.

The full horror of what had happened only unravelled in the coming days and years.

On Lewis, there followed what they call the great silence. Nobody spoke of it at all for five decades and it is only in the last few years that the full story has come out.

Why the silence? Anger, maybe. A whole generation of the island’s men had been lost. Women and children would have found themselves abandoned at a time when crofting was struggling.

For some of the survivors, a sense of guilt that they had made it but others had perished must have felt overwhelming. Such was their sense of remorse that more than a dozen emigrated.

The island’s agony was only heightened by the official response to the disaster. There were serious questions to answer.

Why was the ship so overcrowded? Why was there no lookout? Why was the yacht unaccompanied? How did the captain end up wearing two life belts when others had none? What about the broken searchlight?

And why was the commander who oversaw the Iolaire disaster promoted and then retired without any sanction?

An Admiralty enquiry, which was rushed through in just two days, could find no satisfactory explanation for the disaster.

Its inconclusive findings generated great ill-feeling among the community on Lewis prompting accusations of a ‘whitewash’.

For his part, John Finlay MacLeod, who was 32 at the time of the tragedy, returned to his life as a boatbuilder and lived out his days at the family croft at Port of Ness.

He remained a deeply humble man and rarely spoke about the Iolaire or his part in it.

The few fragments we did glean were passed down through his brother, my great-grandfather, who had left Lewis before the Great War and served as minister in the Free Church at Partick in Glasgow.

It was his daughter, my grandmother, Catherine, a retired Glasgow GP, who would occasionally mention the link – although neither she, nor my mother, Anne, who studied at Glasgow School of Art before meeting my Welsh father, Rees Bryant, on a Spanish holiday, ever looked into it in any detail.

It was only during casual conversations with my friend Torcuil Crichton, a former journalist and Labour’s candidate for the Western Isles, that my interest was piqued.

During lockdown, I began researching my family tree and was astonished to uncover not only John Finlay’s role in the Iolaire, but also the fact that I had an entire family of Gaelic cousins I never knew about.

On my way north to Lewis, I was introduced to one of John Finlay’s grandsons, my cousin, John Neil MacLeod, at his Glasgow restaurant Crabshakk; then met his brother, Iain MacLeod, at the Ness Historical Society.

There, in the presence of the wonderfully authoritative founder member and archivist Annie MacSween, I was shown pictures of my relatives – my great-grandfather in his dog collar, and his parents.

I feel sad I never knew of them until now, their boat-building island life, their Gaelic language and culture, and that I’d never explored my Lewis island connections.

And so I stood at the memorial – fittingly entitled Life Line – armed with all this new family history and felt the strong pull of my ancestor in my veins.

Chris Bryant, in blue, with Torcuil Crichton at Iolaire memorial monument

It all felt very close and very far away at the same time.

Part of me wanted to be able to cry but I felt that would have been wrong because he wouldn’t have done.

Then I felt overcome by a phenomenal rush of anger.

While there was astonishing heroism on the night the Iolaire went down, one is left with the feeling it was entirely avoidable and that terrible injustice followed in its wake.

Our history books are full of many stories of heroism and disaster.

We learn about Trafalgar and Waterloo, of the Somme and Arnhem. But few stories match that of the Iolaire either for official incompetence or plucky heroism.

I hope that now the great silence is over, largely thanks to later generations of islanders who were determined to bring history alive, my great grand-uncle John Finlay MacLeod can be recognised across the country as the great British hero that he was.

Source: Read Full Article