China in an uncomfortable position as the world’s debt collector

When Suriname couldn’t make its debt payments, a Chinese state bank seized the money from one of the South American country’s accounts.

As Pakistan has struggled to cope with a devastating flood that has inundated a third of the country, its loan repayments to China have been rising fast.

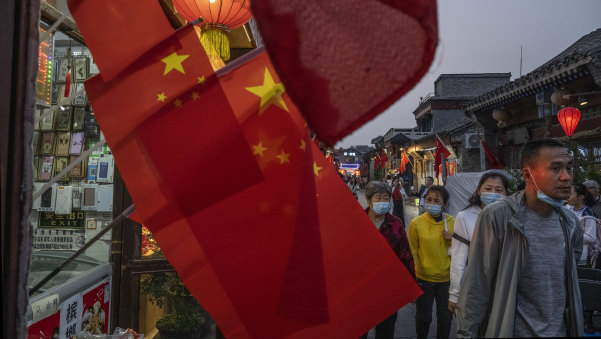

China has been the lender of choice for many developing nations but with global interest rates rising swiftly, debt payments are soaring when these nations can least afford to pay.Credit:Getty

When Kenyans and Angolans went to the polls in presidential elections in August, the countries’ Chinese loans, and how to repay them, were a hot-button political issue.

Across much of the developing world, China finds itself in an uncomfortable position, a geopolitical giant that now holds significant sway over the financial futures of many nations but is also owed huge sums of money that may never be repaid in full.

Beijing was the lender of choice for many nations over the past decade, doling out funds for governments to build bullet trains, hydroelectric dams, airports and superhighways. As inflation has climbed and economies have weakened, China has the power to cut them off, lend more or, in its most accommodating moments, forgive small portions of their debts.

The economic distress in poor countries is palpable, given the lingering effects of the pandemic, coupled with high food and energy prices after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Many borrowed heavily from China. In Pakistan, overall public debt has more than doubled over the past decade, with loans from China growing fastest; in Kenya, public debt is up ninefold and in Suriname tenfold.

The nature of China’s loans is compounding the challenges. China issues far more of its loans to poor countries at adjustable interest rates than Western governments or multilateral institutions. With global interest rates rising swiftly, debt payments are soaring when these nations can least afford to pay. And their weak currencies make it even more costly for many countries to repay China’s loans, almost all of which must be repaid in dollars.

Bureaucratic warfare among powerful government ministries in Beijing has already forestalled any easy solution to the debt problem, and threatens to delay it further. A new slate of ministers will take over in March, likely restarting the process to address debt issues.

China joined France last month in negotiating the outlines of a deal to reduce the debt of Zambia, with the final details still to come. It was done under the so-called Common Framework, a plan by the Group of 20 of the largest advanced and emerging economies to relieve the debt burdens of dozens of poor countries.

In August, Beijing forgave about 0.3 per cent of its loans to African countries. It focused on 20-year-old defaulted debts, money that China was very unlikely to get back.

Western nations are pushing for more such moves, on a much broader scale. “We’re constantly telling China that we want them to come to the table and participate in the Common Framework,” Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said in an interview in Washington.

Pakistan has been hit by devastating floods this year. Overall public debt in the country has more than doubled over the past decade, with loans from China growing fastest.Credit:AP

Chinese officials and academics say the West is too quick to blame China. While most US government financing for poor countries is now done through grants, not loans, American hedge funds have been big lenders to developing countries by buying up their bonds.

China also complains that multilateral lenders such as the World Bank, traditionally led by Americans, and the International Monetary Fund have not forgiven loans to poor countries — although doing so could endanger their credit ratings.

“Western commercial creditors and multilateral institutions, who hold the biggest share of debts, refused to be part of the effort,” Wang Wenbin, a Foreign Ministry spokesperson, said at a ministry briefing a month ago.

China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, has insisted repeatedly that his country is making an earnest attempt to help borrowers. He has also continued to lash out at the Trump administration’s past accusations that China engaged in “debt-trap diplomacy,” that is, lending so much money to poor countries that they would become financially dependent on Beijing.

“You have a lot more influence when you’re providing the loan, than when you’re begging for repayment.”

“These are not ‘debt traps,’ but monuments of cooperation,” Wang said this year.

China and the United States have favoured different approaches to debt troubles. In the past, Beijing has tended to lend more money to some countries, including Argentina, Ecuador and Pakistan, so that they can continue to make payments on existing loans. China’s approach helps these countries afford imports of food and fuel, but leaves them with ever more debt.

The United States prefers requiring government agencies and banks to forgive part of their loans. This was done during the Latin American debt crisis in the 1980s, so that borrowers could afford to repay the interest on the remaining debt.

But this approach requires banks to immediately accept heavy losses, a tough sell in China given its economic slowdown and housing crisis. Weakening home prices and stalled real estate transactions have already left Chinese banks with bad loans to developers and homebuyers.

Those conditions also mean that Chinese banks are reluctant to lend more to countries, including under the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s policy framework for developing countries. Such contracts dropped 5.8 per cent in the first eight months of this year from the same period last year, according to data compiled by China’s Ministry of Commerce.

According to the IMF, three-fifths of the world’s developing countries are now having considerable trouble repaying loans or have already fallen behind on their debts. More than half the world’s poor countries owe more to China than to all Western governments combined.

For now, Chinese officials in poor countries face unpleasant jobs as debt collectors.

“You have a lot more influence when you’re providing the loan,” said Brad Setser, an international payments specialist at the Council on Foreign Relations, “than when you’re begging for repayment.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

The Business Briefing newsletter delivers major stories, exclusive coverage and expert opinion. Sign up to get it every weekday morning.

Most Viewed in Business

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article