Punishment and control: the secret handbook that rules a religion

By Ben Cubby

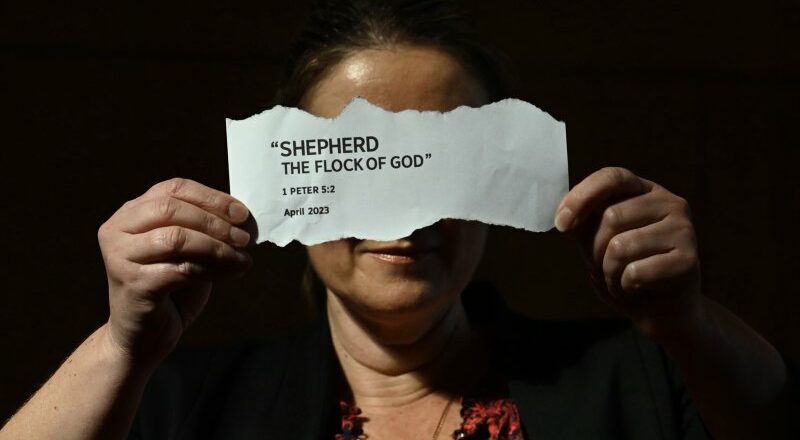

A former Jehovah’s Witness holding a tear out of the 2023 handbook titled “Shepherd The Flock of God”.Credit: Kate Geraghty

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

Australian children in the Jehovah’s Witnesses religion are being trained to avoid life-saving blood transfusions and parents are being coached to thwart court processes that may prevent their children from dying, internal church documents reveal.

An investigation following an inquest into the death of Jehovah’s Witness Heather Winchester, who died in Newcastle after refusing a blood transfusion, has uncovered disturbing practices within the Australian church, including the systems for discipline, punishment and control contained in the secret rule book for church “elders”.

The church’s blood transfusion ban forces people to choose between risking death by refusing treatment or being “shunned” – cut off from family and friends under the church’s strict rules – according to 16 former and current members of the church interviewed and the testimony of many others.

Former Jehovah’s Witness and lawyer Fleur Hawes.Credit: Dan Peled

Some of them believe it has cost hundreds of lives in Australia.

“I think it’s truly dangerous for children, who are not old enough to vote or drive, to be coached about how to convince a judge or doctors about a decision that is potentially life-threatening,” said Fleur Hawes, 32, a solicitor who escaped the religion and is speaking out for the first time.

In public, the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ leadership downplays the impacts of its ban on blood transfusions, which are based on interpretations of Bible passages that say Christians should not eat blood.

“No one is ever obligated to accept or reject a particular medical treatment or procedure,” a church spokesman said.

That is at odds with a secret handbook for church leaders, known as elders, which, according to former Witnesses, most devout members of the sect have never read and women are not even allowed to touch.

The handbook Shepherd the Flock of God and other documents seen by The Sydney Morning Herald set out the lengths the church goes to prevent believers from receiving blood and details the secretive rules that govern the lives of its 70,000 members in Australia and 8.7 million around the world.

You are to abstain from food sacrificed to idols, from blood, from the meat of strangled animals and from sexual immorality.

“I had to say to the doctors that I didn’t want a blood transfusion, but deep down I really did,” said Sarah, a former Witness who refused a blood transfusion while a member and agreed to speak under a pseudonym because she still has family members in the church.

“I had complications and emergency surgery. I was so scared. Nobody wants to say ‘no’ to a transfusion. Nobody should ever be put in that position. It’s a despicable teaching, a gross misinterpretation of a dietary requirement in the Bible.”

Sarah left the church and was shunned. “I lost my whole world overnight,” she said. “I see my parents or friends in a supermarket and they turn their back on me.”

According to the handbook, a 290-page document issued to the church’s leaders earlier this year, elders must direct parents in the sect to read and follow the instructions in a church manual on blood issues before their child undergoes a hospital procedure.

“Firm conviction is vital because a well-meaning doctor may adamantly claim that blood will improve a child’s condition,” the manual says. “Parents must be firmly resolved to ‘abstain from blood’ by refusing it for their children.”

Parents are told to seek out a co-operative doctor and “train their children to defend their faith”.

Former Jehovah’s Witnesses in Sydney.Credit: Kate Geraghty

The manual anticipates the possibility of a court order requiring a blood transfusion for their child in a life-saving situation and coaches them to do everything they can to stop their child receiving blood.

“A wise parent anticipates court involvement,” the manual says. “Parents can inform the court that they are refusing blood on deeply held religious grounds but are not refusing medical care and have no intention of ‘martyring’ their child.”

The manual notes that “this setting may not be the best time for parents to mention their strong faith in the resurrection, as this may convince the judge that they are unreasonable … If a court order is issued despite one’s best efforts, continue to ask the physician not to transfuse and argue that non-blood alternative treatments be utilised.”

The spokesman denied that there was a contradiction between the church’s internal rules on blood and its public statements about free choice.

“The suggestion that each Jehovah’s Witness will only obey God’s commands because of some perceived threat of expulsion, and not his own personal decision to obey divine law as he understands it, is offensive,” the spokesman said.

“It is a rare occurrence for one of Jehovah’s Witnesses to consent to a blood transfusion for himself or his child. The circumstances and reasons behind such a decision are unique to the person and often associated with coercion or pressure from medical staff.”

Parents must be firmly resolved to ‘abstain from blood’ by refusing it for their children.

He said the church only becomes involved at the request of a patient and does “not monitor, screen or track or otherwise record the personal medical decisions of others”. The church will cease any involvement if a patient is contemplating a transfusion, the spokesman said.

According to the handbook, elders pass the name, age, and telephone number of a congregation member who is to undergo medical treatment to the church’s regional hospital liaison committee.

These committees are groups of elders with no specialist medical training appointed to provide pastoral care to church members and sometimes intercede with doctors if there is a possibility of blood products being used in treatment.

Elders must inform the committee of “the spiritual standing of the publisher [the patient] and his family and whether unbelieving family members are involved”.

The elders’ handbook explains how the hospital liaison committee is tasked with helping the patient with “selecting a competent and co-operative doctor”. Parents, pregnant women and older people, “who may be particularly vulnerable to intimidation” on receiving transfusions should be paid special attention, the handbook says.

“When there is a crisis, elders may consider it advisable to arrange a 24-hour watch at the hospital, preferably by an elder with the patient’s parent or another close family member,” according to one church publication advising members on health issues. “Blood transfusions are often given when all relatives and friends have gone home for the night.”

Sherrie D’Souza left the Jehovah’s Witnesses in 2017.Credit: James Brickwood

Being watched by the church while facing life-saving surgery puts patients and families under extreme pressure, former patients said.

“There is no personal, private, voluntary process whereby I or any Jehovah’s Witness could have made or can make an informed decision about blood transfusions,” said Deborah, who has left the church but sought anonymity because her family are members who face being cast out of the religion if her identity was made public.

Another former Witness, Sherrie D’Souza, described rushing to Liverpool Hospital with her mother in 2012 when her elderly father was in desperate need of a transfusion.

“The fact that you’ve got a hospital liaison committee elder there means you can’t ask the questions you want to ask,” D’Souza said. “You are not at liberty to have a conversation with medical professionals. I wanted to say ‘if he needs blood, do it’. I didn’t even get that chance.

“By the time I got there, [the elder] was already there, speaking to the doctors. I remember him asking about blood alternatives. [When asked about transfusions] the elder said ‘that’s not something that’s going to be accepted’.”

D’Souza’s father survived. She said: “The doctors were standing there telling us ‘We’ve stopped the bleeding now, but he needs blood. If he has another bleed and doesn’t have blood we’ll be calling you to say goodbye’.

“How I feel about it now I know the whole teaching is bullshit: It makes me so mad that the religion has such a level of control.”

Solace, structure and ‘new light’

The suburb of Denham Court in Sydney’s semi-rural south-west is home to a private complex dubbed Bethel that houses the Australian branch office of the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

The secure site contains accommodation for several hundred people, printing facilities for the Watchtower magazine and a life-size mock-up of a Middle Eastern-style village, which is used for making instructional films about Bible stories.

This aerial view shows a Middle Eastern-style village constructed by the Jehovah’s Witness religious group in Denham Court in south-west Sydney. Credit: Seven News

According to people who have lived there, Bethel residents live semi-monastic lives governed by arcane rules.

They must be sparing in the use of elevators – “those who need to go up or down more than three flights of stairs are permitted to use them” – and leave doors wide open if unmarried people of the opposite sex are in the same room.

If they “assume an independent attitude” it is grounds for reproval, according to the Bethel rule book. Also banned is “clothing that brings worldly sloppiness or sensuality into the Bethel family. T-shirts bearing slogans are unacceptable at Bethel”.

At dinner “it will be appreciated by others if when the food is passed, you take only a proportional amount of what is in the dish”.

Some modern technology is frowned upon, however, “the telephone is a very helpful instrument that can be used to our advantage [but] please make your conversation brief”.

Parents can inform the court that they are refusing blood on deeply held religious grounds but are not refusing medical care and have no intention of ‘martyring’ their child.

Church members said the organisation can provide believers with a sense of solace and community, and followers share many mainstream Christian beliefs.

One distinguishing feature is the belief that the end of the world is imminent and will soon be replaced by God’s kingdom on earth, and that only 144,000 people will go to heaven.

The local religion is a branch office of the church’s global headquarters in Warwick, New York. It takes instructions on doctrine, policy and organisation from a small group of male elders in the US referred to as the governing body, who are at the top of the religion’s pecking order.

The Australian church owns a large property empire, but its financial affairs are opaque. It controls a series of registered charities and non-profit corporations, many of which are considered too small to be required to make financial disclosures.

Its main registered charity, Watchtower Bible & Tract Society of Australia, takes donations and bequests and enjoyed a healthy financial position in 2022, with $10.4 million in assets.

The Bethel headquarters in Sydney and each congregation is controlled by a group of all-male “elders”, though the church does not routinely publish the names of all those in leadership positions. If an elder breaches rules he can be removed from his role or kicked out of the church. The term for this is “deleted”.

There is no place for women in the upper levels of the church hierarchy.

All members of the church are encouraged to engage only with church-approved literature, and seeking higher education can be grounds for discipline and punishment. According to the elders’ handbook, an elder may have his position reviewed if “he or a member of his household pursues higher education”.

Believers are taught that Satan has controlled the world since 1914, and only devout Jehovah’s Witnesses will survive a looming Armageddon.

Former Jehovah’s Witness Ben Lynch.Credit: Kate Geraghty

As at least four much-heralded prophecies for the date of Doomsday came and went in the past century, the church developed the practice of continually rewriting its own history and spiritual instruction manuals, in part to gloss over failed predictions. Updated information is referred to as “new light”.

“At the church I went to, there was a library next to the meeting room,” said Ben Lynch, 24, who left the religion in his late teens after learning about the science of evolution at school.

“It was quiet and I liked it there with all the books. Not necessarily studying, just flipping through the pages, enjoying the books. One day, the elders came in and started taking books off the shelves. What had happened was that Bethel had just said we have got ‘new light’ and decreed that the old books had to be destroyed.

“I asked what was going on, why they were taking the books away, and the elders just said ‘we don’t need them any more’. That was that,” Lynch said.

“I’ve read Nineteen Eighty-Four, so I know what it means to describe it as Orwellian. They’re always destroying information, rewriting their literature, and everyone has to believe it’s always been that way. It’s like the Ministry of Truth.”

Raymond Franz, a former member of the church’s global governing body, was cast out for questioning the rules.

The latest list of church literature that has been deemed unsafe was circulated among Australian congregations last month. The list includes more than 50 of the organisation’s own books and pamphlets to be discarded or in some cases destroyed.

The church’s rules on blood have also been revised many times. The sect’s ban on transfusions was introduced in 1945, and the church later decreed that a Jehovah’s Witness who received blood would be “disfellowshipped” or “disassociated” – cast out of the church and shunned by everyone in it.

The ruling is based on Bible passages in Genesis and Leviticus which say Christians should not eat blood, and an ambiguous passage in Acts 15:20 which says, “You are to abstain from food sacrificed to idols, from blood, from the meat of strangled animals and from sexual immorality”.

Some Christians have interpreted this to mean abstaining from blood within the context of food. Jehovah’s Witnesses have extended the meaning to include blood transfusions, which were unknown when the Bible was written.

The rules have subsequently been tweaked many times, permitting medical use of many artificially separated “blood fractions” – products derived from blood, such as haemoglobin – but not blood itself.

This led Raymond Franz, a former member of the church’s global governing body who was cast out for questioning the rules, to compare the blood edict to banning ham and cheese sandwiches but allowing the eating of bread, ham and cheese.

‘Barely seen my family since’

The blood rules can lead to confusion for Jehovah’s Witnesses and doctors.

At a coronial inquest in May, deputy state coroner David O’Neil heard evidence that Hunter Valley woman Heather Winchester, 75, was wheeled into theatre for a routine operation with an anaesthetist who believed she had consented to receive some blood fractions if required and a surgeon who believed she had refused all blood products.

Winchester, who was a doorstop convert to the Jehovah’s Witnesses, was determined to follow the church’s teachings, her daughter Elizabeth told the inquest. “She felt that this was what the church wanted her to do.”

Gynaecologist Adrienne Searle, who was working at John Hunter Hospital in Newcastle when Winchester was transferred there after bleeding following two earlier surgeries, said she had made it clear that Winchester’s life was at risk if she refused a transfusion.

Gynaecologist Dr Adrienne Searle was working at John Hunter Hospital in Newcastle when Heather Winchester was transferred.

“I have never in my career counselled anyone so strongly about their risk of death,” Searle told the inquest. But Winchester would not receive blood. “I have had sleepless nights,” Searle said.

Winchester died four days after her initial operation, on September 27, 2019. The coronial findings into her care and medical treatment are yet to be finalised.

Former Witnesses recall being trained as children to refuse blood at all costs and to always carry a “no blood” card – a form of advanced medical care directive.

“As a nine-year-old child before having a small abdominal operation, I repeated to doctors what my parents had already told them – that I couldn’t have a blood transfusion,” Deborah said.

Hawes recalls carrying a card as a child and described being coached to refuse transfusions many times in twice-weekly congregation meetings.

“You’re in a small group setting talking about refusing blood because it’s what Jehovah wants,” she said. “There’s no option to ask questions.”

Hawes, who was regarded as a rising star of the church in her early teens and spoke at church conventions in front of thousands of people, started veering away from the Jehovah’s Witnesses because she felt it was sexist and oppressive.

“I’d learnt about first- and second-wave feminism at school,” she said. “I wasn’t just going to live out my life to serve men.”

Former Jehovah’s Witness and lawyer Fleur Hawes, 32.Credit: Dan Peled

Her parents wanted to home-school her and that was the catalyst for Hawes leaving. She was cast out and shunned by her family at 16.

“I remember walking to the street corner with my schoolbag on my back, going to the fish and chip shop and calling my friend’s mum. That was it. I worked lots of jobs, slept on couches, made my way through school. I have barely seen my family since.”

Shunning is a “weapon” that forces church members to conform, former members said. Interviewees described a consistent pattern of congregation members reporting any unorthodox behaviour to elders, and blood policy being policed by elders and the hospital liaison committees.

An elder serving on a hospital liaison committee, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said the committee’s main role was providing emotional support to Jehovah’s Witnesses and talking with medical staff about the sect’s requirements.

“The aim is to give people information and ensure people know that there are alternatives to blood … We’re not there to spy on anyone, we aim to help.”

Former church elder John Viney served on hospital liaison committees for 15 years in Britain, which has the same church structure as Australia.

“I was a faithful and loyal JW through and through,” he said. “I saw my role as actually helping save lives of JW patients in providing information on how the medical situation could be handled to meet the patient’s viewpoint but also provide medical needs from a hospital standpoint.”

Viney’s view of the church soured after he was forced to shun his own daughters, and he now campaigns against the shunning of children.

“The shunning of people you love, completely avoiding them, is a killer as far as I am concerned. I always thought this and had trouble accepting it, but such was the cult mentality that not only did it happen to my family but as an elder, I disfellowshipped others … It’s a wicked cult control mechanism.”

Judging repentance is not simply a matter of determining whether the wrongdoer is weak or wicked.

The church’s spokesman said: “How each parent chooses to raise their own children is up to them and naturally many will choose to raise them in accordance with their own religious beliefs. When it comes to medical care, Witness parents seek out the best possible medical care for their children.”

It is unclear how many people may have died as a result of refusing transfusions in line with the sect’s blood policy. The Red Cross estimates one in three Australians require a blood transfusion at some point in their lives.

Since leaving the church, Sherrie D’Souza has helped run a support group, Recovering From Religion, which calls for watertight confidentiality around a patient’s medical decision-making, so church authorities cannot know if a person has agreed to a blood transfusion.

“The hospital liaison committees invade people’s privacy,” she said. “There aren’t any statistics to tell us how many people have died. Anecdotally, there are many.”

A global church whistleblower group based in the US, Advocates for Jehovah’s Witnesses for Reform on Blood, has attempted to estimate the death toll in which the refusal of blood transfusions was a major or contributing factor, basing its research on data about transfusions in the wider community. Reaching precise figures is not possible because of a lack of data due to patient privacy.

“The estimate of annual deaths in Australia would be between 10 and 18 assuming 68,000 members,” the group’s spokesman, who goes by the pseudonym Lee Elder, said.

“If we assume the ratio of members has been relatively the same with the average number of worldwide members over the past 62 years, we can extrapolate that somewhere between 632 and 1096 Australian Jehovah’s Witnesses have likely died prematurely as a result of following the Watchtower blood policy.”

The Jehovah’s Witnesses spokesman said the idea that the blood policy had led to any deaths was “completely unfounded” and said medical literature backs up the church’s view that patients have better outcomes when they avoid blood transfusions.

Many peer-reviewed studies suggest transfusions should only be used when essential, but no studies support the idea that they should be banned.

NSW Health said it “respects and upholds the wishes of any individual and will adhere to their choices regarding the administration of blood products”.

The department did not directly respond to questions about whether hospital liaison committees played a role in policing the medical care choices of church members, or what steps were taken in hospitals to make sure Jehovah’s Witness patients were not making decisions about medical care under duress.

“As established in Australian case law, all adult patients with capacity have the right to refuse any medical treatment, even in cases where that decision may lead to their death,” a NSW Health spokesperson said.

“Similar to a person giving consent to medical treatment, a refusal of treatment must be freely given, specific and informed.”

According to the elders’ handbook, if blood is administered to a patient, elders at the patient’s congregation are required to set up a committee to “determine the individual’s attitude”.

In a section of the handbook devoted to judging repentance after a member of the religion is deemed to have broken the rules, elders’ committees are given some guidelines.

“The committee must be convinced that the wrongdoer has a changed heart condition, that he has a zeal to right the wrong, and that he is absolutely determined to avoid it in the future,” the handbook says.

“Judging repentance is not simply a matter of determining whether the wrongdoer is weak or wicked. Weakness is not synonymous with repentance.”

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.

Most Viewed in National

Source: Read Full Article